THE MAN WHO LOOKED AT THE GROUND

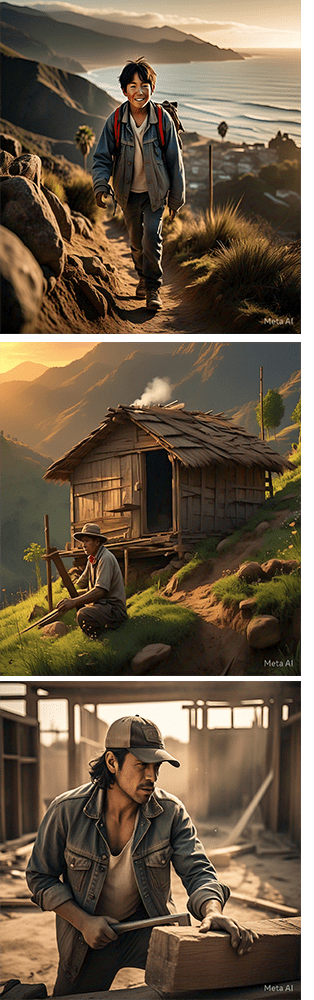

Este era chato (de baja estatura) y tímido, con grandes rasgos indígenas. Vivió marginado todo el tiempo, desde que vio la luz de este mundo. El primer opresor fue su padre, su madre era callada y sin carácter. Conoció el abuso en su máxima expresión. Regularmente y siendo niño, se preguntaba cuál era el objetivo de su paso por este mundo de dolor y miseria.

He was short and shy, with strong indigenous features. He lived marginalized the entire time, ever since he was born. His first oppressor was his father; his mother was quiet and spineless. He experienced abuse in its fullest form. As a child, he regularly wondered what the purpose of his time in this world of pain and misery was.

Nació en las alturas de Junín, fue el último de doce hermanos, quienes nacieron uno tras otro. En la sierra, los niños desde que pueden caminar, ya son jalados a las chacras para el trabajo duro. Todos sus hermanos desde niños dominaban las labores del campo. Ninguno iba a la escuela, pues su padre decía que era una pérdida de tiempo.

He was born in the highlands of Junín, the youngest of twelve children, born one after the other. In the mountains, children are pulled out to the fields for hard labor from the time they can walk. All of his siblings mastered field work from childhood. None of them went to school, as their father said it was a waste of time.

Jacinto, el personaje de nuestro relato, extrañamente, no se conformaba con su suerte; él quería estudiar y ser un gran profesional, pero al lado de su padre no sería más que un siempre campesino, por eso a sus doce años, al saber que su hermano mayor se fue a Argentina, él también abandonó el seno familiar y deambuló a su suerte, buscando trabajos eventuales para poder subsistir.

Jacinto, the character in our story, strangely enough, wasn’t content with his lot. He wanted to study and become a great professional, but next to his father, he would always be a peasant. So at the age of twelve, upon learning that his older brother had left for Argentina, he too left the family and wandered to his fate, looking for odd jobs to make ends meet.

Estuvo por Lima, la capital del Perú un tiempo; luego, al cumplir los dieciocho años, llegó a Trujillo. En esa época, el cerro Cabras era virgen, no había presencia humana en sus faldas, solo en las partes céntricas del distrito La Esperanza, por allí cogió un lote pequeño, donde a duras penas fue levantando su vivienda, junto a los primeros moradores de la parte alta de aquel distrito. “El cholo triste” le decían en el polvoriento barrio, pues siempre se le veía cabizbajo y nunca sonreía, cuando le hacían cosquillas o le contaban algún chiste colorado, esbozaba una fingida sonrisa que le duraba poco tiempo. Todos esos años alejado del seno familiar había trabajado sobre todo como ayudante de construcción, esforzando su pequeño cuerpo al máximo, lo que le causó severos problemas en su columna vertebral y en los pulmones, impidiendo a su vez desarrollarse con normalidad. Fue maltratado y explotado, muchas veces concluida su labor y siendo menor de edad, no recibía la paga que le correspondía, y no tenía a dónde y a quién pedir haga justicia.

He spent some time in Lima, the capital of Peru; then, when he turned eighteen, he arrived in Trujillo. At that time, Cabras Hill was untouched; there was no human habitation at its foothills, only in the central parts of the La Esperanza district. There, he acquired a small plot of land, where he built his home with great difficulty, alongside the first residents of the upper part of that district. «The sad cholo,» they called him in the dusty neighborhood, because he was always seen with his head down and never smiled. When someone tickled him or told him a dirty joke, he would only manage a fake smile that didn’t last long. All those years away from his family, he had worked primarily as a construction assistant, pushing his small body to the limit, which caused severe problems with his spine and lungs, in turn preventing him from developing normally. He was mistreated and exploited, often after completing his work and being a minor, he did not receive the pay he was owed, and he had nowhere and no one to turn to for justice.

Decidió en Trujillo, alternar su trabajo, con los estudios en un centro de educación básica alternativa a lo cual le puso mucho empeño. Sus compañeros de clase que eran despiertos y algunos abusivos, siempre lo molestaban, allí conoció a Carola, una joven cinco años mayor que él, era cristiana, y se convirtió en su alma protectora frente a sus compañeros que le hacían bullying constantemente.

In Trujillo, he decided to combine his work with his studies at an alternative elementary school, which he worked hard at. His classmates, who were bright and sometimes abusive, constantly bothered him. There, he met Carola, a young woman five years his senior who was a Christian, and she became his protector against his classmates, who constantly bullied him.

―¿Por qué eres tan callado? ―le preguntaba.

―Tienes que aprender a defenderte, tienes que despertar. Claro que no está bien ir peleando con toda la gente, pero tienes que mejorar tu actitud. Acá en Trujillo, vas a encontrar gente buena, pero también gente muy mala y te tratarán como tu permitas que te traten ―le decía Carola.

-«Why are you so quiet?» I asked.

-«You have to learn to defend yourself, you have to wake up. Of course, it’s not right to go around fighting with everyone, but you have to improve your attitude. Here in Trujillo, you’ll find good people, but also very bad people, and they’ll treat you however you allow them to treat you,» Carola told her.

―No solo en Trujillo hay gente mala, los malos están por todas partes. En mi propia casa me trataban mal ¿qué puedo esperar de los demás? ―decía Jacinto con voz apagada.

«It’s not just Trujillo that has bad people; bad people are everywhere. In my own home, they treated me badly. What can I expect from others?» Jacinto said in a subdued voice.

―Solo tienes que saber con quién juntarte Jacinto, alejarte de la gente negativa y reunirte con gente que te aprecie y valore ―insistía Carola, con voz cálida y reflexiva.

«You just have to know who to hang out with, Jacinto, stay away from negative people and hang out with people who appreciate and value you,» Carola insisted, her voice warm and thoughtful.

―Es difícil Carola, cómo puedo decidir con quiénes estudiar en el colegio, allí están los malos y también estás tú; en el trabajo es la misma cosa, hay gente mala y abusiva, yo no decido con quién trabajar, ni quién sea mi patrón; a veces quisiera irme lejos, muy lejos. Uno de mis once hermanos fue a Argentina, no volví a saber nada de él, supongo que le ha ido bien, ya no se comunica con nosotros, quisiera ir a buscarlo.

«It’s difficult, Carola. How can I decide who to study with at school? There are the bad guys there, and there’s you too. At work, it’s the same thing. There are mean and abusive people. I don’t decide who to work with, or who my boss is. Sometimes I wish I could go far away, very far away. One of my eleven siblings went to Argentina. I never heard from him again. I suppose he did well. He doesn’t communicate with us anymore. I’d like to go look for him.»

―Mírame Jacinto ¬―le cogió el mentón e hizo que le mire a los ojos― ¿qué te hace suponer que en Argentina te tratarán mejor?, el problema, no está en los demás, podrás ir al último rincón del mundo y te tratarán igual o peor.

―Look at me, Jacinto—―he grabbed his chin and made him look into his eyes—―what makes you think that in Argentina they would treat you better? The problem isn’t with the others. You can go to the farthest corner of the world and they will treat you the same or worse.

―Qué hago entonces, me suicido ―dijo con voz lastimera.

«What do I do then, commit suicide?» he said in a pitiful voice.

―No Jacinto, lo primero que tienes que hacer es decirte a ti mismo: “Yo soy hijo de Dios, hecho a su imagen y semejanza y merezco respeto”, y lo segundo es dejar de mirar al suelo, aprende a mirar de frente, no temas mirar a los ojos de los demás, mira el cielo infinito, allí puedes encontrar respuestas a muchas de tus preguntas, pues lo que verás, es la inmensidad de Dios.

―No Jacinto, the first thing you have to do is tell yourself: “I am a child of God, made in his image and likeness and I deserve respect,” and the second is to stop looking at the ground, learn to look straight ahead, do not be afraid to look into the eyes of others, look at the infinite sky, there you can find answers to many of your questions, because what you see is the immensity of God.

―Quizás tengas razón Carola, pero no puedo dejar de mirar al suelo.

―¿Pero, por qué? ―insiste Carola.

«Maybe you’re right, Carola, but I can’t stop looking at the floor.»

«But why?» Carola insists.

Jacinto, para justificarse, le responde:

Jacinto, to justify himself, answers:

―Porque ya son varias veces que me he encontrado dinero por tener esta manía de mirar al suelo, sobre todo en fechas de Navidad y Año Nuevo, la gente va a las fiestas y se emborrachan a morir, fíjate que una vez me encontré doscientos soles.

«Because I’ve found money several times because of this habit of staring at the ground, especially around Christmas and New Year’s. People go to parties and get drunk. Just think, I once found two hundred soles.»

―¿Es en serio?, entonces de hoy en adelante también voy a mirar al suelo igual que tú.

¬―¡Jajajajaja! ―ambos rieron por un buen rato; era la primera vez en toda su vida que Jacinto había reído a sus anchas y notó lo bien que eso hace al alma.

«I’m serious, so from now on I’m going to stare at the ground just like you.»

«Hahahaha!» They both laughed for a long time; it was the first time in his entire life that Jacinto had laughed so freely, and he noticed how good it is for the soul.

―¿Por qué te interesas tanto por mí, Carola? Si solo soy un cholo feo y tonto.

―Porque creo que ambas cosas se pueden arreglar Jacinto; lo feo, con unos buenos retoques estéticos en el rostro, y lo tonto, con unos buenos retoques en tu alma.

«Why are you so interested in me, Carola? I’m just an ugly, dumb cholo.» «Because I think both things can be fixed, Jacinto; the ugly, with a few cosmetic touches to your face, and the dumb, with a few touches to your soul.»

―¡Jajajajaja! ―vuelven a sonreír y se abrazan y en ese efusivo momento, Carola roza los labios de Jacinto y se dan un beso, de lo cual ambos terminan ruborizados.

«Hahahahaha!» They smile again and hug, and in that effusive moment, Carola touches Jacinto’s lips and they kiss, which makes them both blush.

―Supongo que ya somos enamorados verdad ―dijo Jacinto.

«I guess we’re in love now, right?» Jacinto said.

―Supongo que me estás pidiendo que sea tu novia verdad ―dijo Carola y volvieron a sonreír otro rato.

«I guess you’re asking me to be your girlfriend, right?» Carola said, and they smiled again for a while.

―Es la primera vez que me siento bien con alguien Carola, ya no quiero ir a Argentina, de ahora en adelante cambiaré mi actitud ante la vida.

«This is the first time I’ve felt good around someone, Carola. I don’t want to go to Argentina anymore. From now on, I’ll change my attitude toward life.»

―Si, pero sigue mirando al suelo por favor a ver que más encuentras ―¡Jajajajaja! Siguen riendo escandalosamente.

«Yes, but please keep looking at the floor and see what else you find.» «Hahahaha!» They continue laughing outrageously.

Jacinto y Carola se casaron. Él no pudo terminar sus estudios pues le faltaban muchos años, pero Carola si los terminó. Ella estudió una carrera técnica de Enfermería y se hizo profesional; el trabajaba en construcción civil, que era el oficio que mejor había aprendido. Tuvieron tres hijos quienes se criaron en el seno de una familia cristiana. Fue Carola quien los acercó a Dios y a sus creencias y los niños crecieron en estatura y sabiduría.

Jacinto and Carola married. He couldn’t finish his studies because he had too many years to go, but Carola did. She studied nursing and became a professional, while he worked in civil construction, the trade he had learned best. They had three children who were raised in a Christian family. It was Carola who brought them closer to God and their beliefs, and the children grew in stature and wisdom.

Jacinto “el cholo triste”, ya no era tan triste, pues decía que había hallado el gozo en el señor Jesús y poco a poco se le fue perdiendo dicho apelativo en su barrio de La Esperanza. Lo que no perdió fue la costumbre de mirar al suelo, por petición de Carola, quien también hacía lo mismo; pues eso de encontrar dinero en el suelo sí era cierto y ella misma lo había comprobado, pues cuando iba de compras al mercado, más de una vez encontró un fajo de dinero que para ella era un regalo de Dios.

Jacinto, «the sad cholo,» was no longer so sad, for he said he had found joy in the Lord Jesus, and little by little, he lost that nickname in his neighborhood of La Esperanza. What he didn’t lose was his habit of looking at the ground, at Carola’s request, who also did the same. Finding money on the ground was true, and she herself had confirmed it. When she went shopping at the market, she had more than once found a wad of money that, to her, was a gift from God.

El Cholo triste, vivió un feliz matrimonio al lado de la mejor compañera que Dios le dio, “Carola” y sus tres hijos que eran su adoración. A los cincuentaicuatro años, falleció, víctima de cáncer al pulmón, los desarreglos que había hecho a su corta edad le pasaron factura. La familia lloró su partida, pero aceptaron los designios de Dios, prometiendo ser buenos para encontrarse con él allá en el cielo.

The sad Cholo lived a happy marriage with the best companion God had ever given him, «Carola,» and his three children, who were his adoration. At the age of fifty-four, he died of lung cancer; the messes he had made at such a young age had taken their toll. His family mourned his passing, but accepted God’s plan, promising to be good to him in heaven.

Descubre más desde LA AGENCIA MUNDIAL DE PRENSA

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.