IMAGINED STORIES; The poet died at dawn

¿Por qué, Raúl, tu poeta debió morir al amanecer? Sé que no responderás la pregunta porque no estás aquí; ya acabó el tiempo de las conversaciones. Además, aunque quisiera saberlo, es también verdad que debería entrar en tu mismidad, en tus emociones, en tu imaginación. Y eso es imposible.

Why, Raúl, should your poet have died at dawn? I know you won’t answer the question because you’re not here; The time for conversations is over. Furthermore, although I would like to know, it is also true that it should enter into your self, into your emotions, into your imagination. And that is impossible.

Así que, Raúl, no queda sino interpretarte, lo que, de algún modo, es inventar tus pensamientos nacidos de quién sabe cuántos maravillosos instantes. Es decir —porque ¿de qué valdría la pretensión de realmente saber?— armarme de unas ideas que, aunque mías, jamás serán las que condujeron tu sabia mano a escribir que el poeta, tu poeta, tal vez no se fue como quiso.

So, Raúl, all that remains is to interpret you, which, in a way, is to invent your thoughts born from who knows how many wonderful moments. That is to say—because what would be the point of pretending to really know?—to arm myself with ideas that, although mine, will never be those that led your wise hand to write that the poet, your poet, perhaps did not go as he wanted.

«Sin un céntimo, tal como vino al mundo, murió al fin en la plaza frente a la inquieta feria».

«Without a cent, just as he came into the world, he finally died in the square in front of the restless fair.»

Pero, Raúl, se me ha ocurrido que, estés donde estés, celebrarás este esfuerzo derrotado de antemano. Es que tú supiste como pocos, en tantas madrugadas insomnes y alcohólicas, no solo de derrotas sino de cuánto cuesta vestir la piel de otro con la conmovedora intensidad que tú lo hiciste. ¿Por qué en un amanecer? Tal vez sean las pocas horas en que deba ocurrir toda muerte de un ser intenso, sensible; la noche ha dejado de ser noche, las primeras, difusas luces buscan abrirse paso y se expone ante uno la gran paradoja: un día más, la necesidad de seguir pensando mundos que no serán, o que fueron y nos hirieron de un modo cruel, la latencia del sufrimiento, la esperanza improbable de un destino que se modifica, la comprensión de los otros. O el cansancio, definitivo, final.

But, Raúl, it occurred to me that, wherever you are, you will celebrate this defeated effort in advance. The thing is that you knew like few others, in so many sleepless and alcoholic early mornings, not only about defeats but about how much it costs to dress the skin of another with the moving intensity that you did. Why at dawn? Perhaps they are the few hours in which every death of an intense, sensitive being must occur; The night has ceased to be night, the first, diffuse lights seek to make their way and the great paradox is exposed before one: one more day, the need to continue thinking about worlds that will not be, or that were and hurt us in a cruel way, the latency of suffering, the improbable hope of a destiny that changes, the understanding of others. Or the final, definitive tiredness.

«Velaron el cadáver del dulce vagabundo dos musas, la esperanza y la miseria./ Fue un poeta completo de su vida y de su obra,/ escribió versos casi celestes,/ casi mágicos, de invención verdadera/ y como hombre de su tiempo que era,/también ardientes cantos y poemas civiles/de esquinas y banderas.»

«Two muses, hope and misery, watched over the corpse of the sweet wanderer./ He was a complete poet of his life and his work,/ he wrote almost celestial verses,/ almost magical, of true invention/ and as a man of his time he «It was,/also ardent civil songs and poems/of corners and flags.»

Un amanecer puede ser triste, muy triste. Algo así como el despertador final para quien ya no resiste vestir andrajos, andar con el calzado roto y los cordones desatados, desaliñado, sin afeitar, mal mirado al pasaje del carnaval ciudadano, apenas hallando cobijo en el banco de esa plaza donde lo sacude la inquieta feria de la mañana. Morir al amanecer por eso. Dejarse morir al amanecer, porque ya no puede escribir más, porque ya lo dio todo —solo falta su esqueleto— y sabiendo que solo lo recordará aquel que lo inventó en su alma y lo expuso para que lo quisieran aunque solo logró soltar lágrimas ajenas de la gran culpa ajena: la indiferencia.

A dawn can be sad, very sad. Something like the final alarm clock for those who can no longer resist wearing rags, walking with torn shoes and untied laces, unkempt, unshaven, frowning upon the street at the city’s carnival, barely finding shelter on the bench in that square where the wind shakes them. restless morning fair. Die at dawn for that. Letting himself die at dawn, because he can’t write anymore, because he already gave everything – only his skeleton is missing – and knowing that only the one who invented him in his soul and exposed him so that they loved him will remember him, although he only managed to let out other people’s tears of the great fault of others: indifference.

«Algunos, los más viejos, lo negaron de entrada./ Algunos, los más jóvenes, lo negaron después. /Hoy irán a su entierro cuatro buenos amigos,/ los parroquianos del café,/ los artistas del circo ambulante,/ unos cuantos obreros,/ un antiguo editor,/ una hermosa mujer…»

«Some, the older ones, denied it at first./ Some, the younger ones, denied it later. /Today four good friends will go to his funeral,/ the café patrons,/ the traveling circus artists,/ a few workers,/ a former editor,/ a beautiful woman…»

Los de siempre, los únicos, incluso los que estuvieron y se fueron y ahora vuelven, flagelándose por no haber hecho todo lo que pudieron; incluso los que se aprovecharon de su locura poética, los que se emocionaron y los que se divirtieron; incluso aquella que él soñó, o creyó que soñó que podría quererlo. Es verdad, Raúl. Estos poetas deben morir al amanecer, como gorriones que el tiempo va congelando sobre las balaustradas y sobre las ramas de los árboles que rodean la plaza. Tu poeta murió como debía. Aquí ya no le aguardaba sino la desesperación y el cansancio final. Tu poeta hizo lo que debía hacer. Y se dejó ir. Pero mañana —porque siempre hay un mañana, Raúl—:

The usual ones, the only ones, even those who were there and left and now return, flagellating themselves for not having done everything they could; even those who took advantage of his poetic madness, those who were moved and those who had fun; even the one that he dreamed, or thought he dreamed, could love him. It’s true, Raúl. These poets must die at dawn, like sparrows that time freezes on the balustrades and on the branches of the trees that surround the square. Your poet died as he should. Here nothing but desperation and final exhaustion awaited him. Your poet did what he had to do. And he let go. But tomorrow—because there is always a tomorrow, Raúl—:

«Mañana…, mañana, florecerá la tierra que caiga sobre él!».

«Tomorrow…, tomorrow, the earth that falls on it will bloom!».

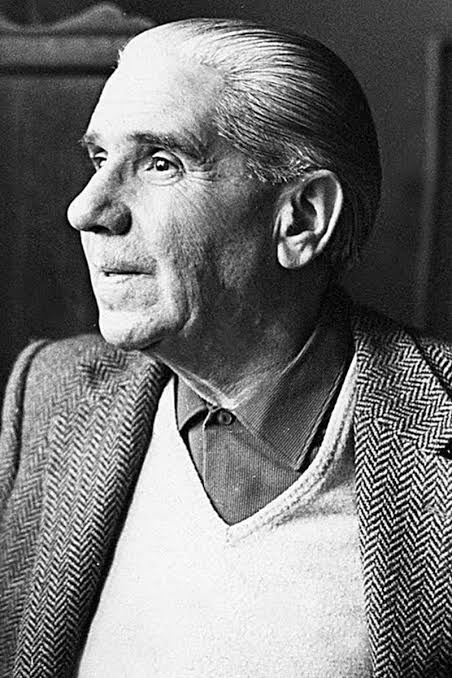

«El poeta murió al amanecer» es, quizás, el poema más conocido y apreciado de Raúl González Tuñón, poeta y periodista argentino considerado uno de los fundadores de la corriente de poesía urbana. Nació en Buenos Aires en 1905 y murió en la misma ciudad en 1974. Escribió en el diario Crítica, perteneció al grupo literario de Boedo pero tuvo amigos entre los escritores del opuesto grupo de Florida. Sus poesías, que reflejan su espíritu de amigo de las gentes, de las mujeres y del vino, además de defensor de los llamados «perdedores sociales», están principales en libros como Miércoles de ceniza, La calle del agujero en la media, El violín del diablo y la serie Poemas de Juancito el caminador.

«The poet died at dawn» is, perhaps, the best-known and most appreciated poem by Raúl González Tuñón, an Argentine poet and journalist considered one of the founders of the urban poetry movement. He was born in Buenos Aires in 1905 and died in the same city in 1974. He wrote in the newspaper Crítica, belonged to the Boedo literary group but had friends among the writers of the opposite Florida group. His poems, which reflect his spirit as a friend of people, women and wine, as well as a defender of the so-called «social losers», are featured in books such as Ash Wednesday, The Street of the Hole in the Stocking, The Violin of the Devil and the series Poems of Juancito the Walker.

Descubre más desde LA AGENCIA MUNDIAL DE PRENSA

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.