Retrospective and present

De nuevo, he querido traer a Culturas del Mundo algo que es complicado considerar como tal, algo para lo que hay que crear la categoría Cultura del Horror. Para ello actualizo una reseña publicada en 2019 de una exposición temporal en el museo madrileño de arte contemporáneo Reina Sofía, que llevó por título “Ceija Stojka: Esto ha pasado”. Una de los millones de historias de los campos de exterminio nazi, en la que no hay judíos, sino gitanos, aquí rescatados del injusto olvido.

Once again, I wanted to bring to World Cultures something that is difficult to consider as such, something for which we must create the Culture of Horror category. To do this, I update a review published in 2019 of a temporary exhibition at the Madrid museum of contemporary art Reina Sofía, which was titled “Ceija Stojka: This has happened.” One of the millions of stories from the Nazi extermination camps, in which there are not Jews, but gypsies, here rescued from unjust oblivion.

En la comparativa de hoy, no hay campos de exterminio, hay campos de refugiados, escuelas, hospitales, sociedad civil bombardeados sistemáticamente durante más de un año, con el pretexto infame de liquidar terroristas de Hamas. Hablamos de Gaza. Hablamos de descendientes de víctimas del Holocausto convertidos hoy en verdugo de inocentes, entre los que se cuentan decenas de miles de niños palestinos. Otra forma de exterminio. Casi un siglo después.

In today’s comparison, there are no extermination camps, there are refugee camps, schools, hospitals, civil society systematically bombed for more than a year, with the infamous pretext of eliminating Hamas terrorists. We talk about Gaza. We are talking about descendants of Holocaust victims who today have become the executioners of the innocent, among whom are tens of thousands of Palestinian children. Another form of extermination. Almost a century later.

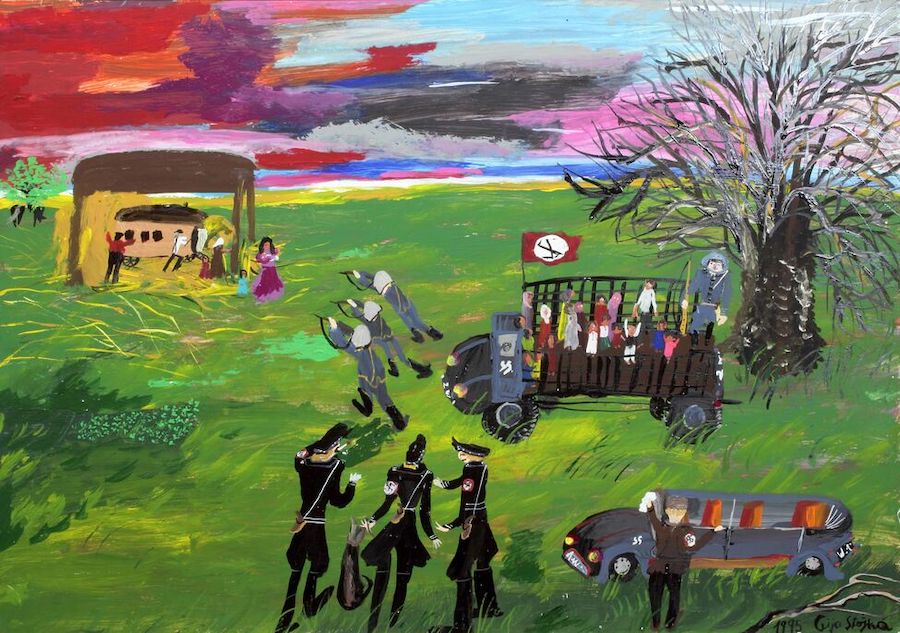

Retrospectiva de la historia de Ceija Stojka. / Retrospective of the history of Ceija Stojka.

El Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía de Madrid (MNCARS) expone un testimonio del genocidio nazi durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el de la gitana austriaca Ceija Stojka, quien sobrevivió al horror de tres campos de exterminio entre 1943 y 1945, Auschwitz, Ravensbrück y Bergen Belsen.

The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid (MNCARS) exhibits a testimony of the Nazi genocide during the Second World War, that of the Austrian gypsy Ceija Stojka, who survived the horror of three extermination camps between 1943 and 1945, Auschwitz, Ravensbrück and Bergen Belsen.

Ceija vivió un silencio postraumático de cuatro décadas. En los años noventa del siglo pasado, mediante escritos, dibujos y pinturas relató, sobre todo por medio de colores y símbolos, su feliz vida anterior al nazismo, la caza de su familia y su clan, los Lovara, de los que solo sobrevivieron cinco de los más de doscientos cincuenta que eran antes del Porrajmos (holocausto).

Ceija lived a post-traumatic silence for four decades. In the nineties of the last century, through writings, drawings and paintings, he recounted, especially through colors and symbols, his happy life before Nazism, the hunting of his family and his clan, the Lovara, of whom only five of the more than two hundred and fifty survived before the Porrajmos (holocaust).

El horror de la sección B-II-e o Campo familiar gitano de Auschwitz, desde marzo de 1943, de donde ella, su madre y una de sus hermanas salieron deportadas en junio de 1944 hacia Ravensbrück, un campo de concentración de mujeres donde eran utilizadas como cobayas, solo unos días antes del exterminio del campo gitano en el campo polaco. En enero de 1945 ella y su madre, Sidi, fueron a parar a Bergen Belsen, donde sobrevivieron a un auténtico apocalipsis.

The horror of section B-II-e or the Gypsy Family Camp of Auschwitz, since March 1943, from where she, her mother and one of her sisters were deported in June 1944 to Ravensbrück, a concentration camp for women where they were used as guinea pigs, just a few days before the extermination of the Gypsy camp in the Polish countryside. In January 1945 she and her mother, Sidi, ended up in Bergen Belsen, where they survived a real apocalypse.

Después de la liberación, tardaron más de tres meses en regresar a Viena. Luego pudieron ir recuperando sus vidas, pero la mente de Ceija, congelada por el horror indescriptible vivido, despertó mucho más tarde.

After liberation, it took them more than three months to return to Vienna. Then they were able to recover their lives, but Ceija’s mind, frozen by the indescribable horror she experienced, woke up much later.

Nunca hubo ayuda para los gitanos, ni reconocimiento oficial de un genocidio que afectó aproximadamente a medio millón de personas en Europa. En Austria el 90 % de la población gitana fue asesinada. Venían precedidos de discriminaciones y persecuciones desde el siglo XV en que los distintos pueblos romaníes se instalaron en Europa. Su nomadismo, su espíritu libre, tampoco ayudó.

There was never help for the gypsies, nor official recognition of a genocide that affected approximately half a million people in Europe. In Austria 90% of the Roma population was murdered. They were preceded by discrimination and persecution since the 15th century when the different Romani peoples settled in Europe. His nomadism, his free spirit, didn’t help either.

Ceija Stojka había nacido en 1933, es decir todo lo que vivió hasta 1945 sucedió durante los primeros doce años de su vida. Su relato sobrecogedor no es la narración del horror vivido por una familia, es la de todo el colectivo gitano, de los supervivientes y de las víctimas mortales. Tiene el valor añadido de poner en primera línea lo ignorado, lo borrado como si no hubiera existido. Sería extraño encontrar a alguien que no haya oído hablar de la Shoáh, pero ¿quién ha oído hablar del Porrajmos? Gracias a ella el gobierno austriaco ha reconocido oficialmente el genocidio y el de Angela Merkel reconoció en 2012 el genocidio de los pueblos romaní y sinti perpetrado por el régimen nazi y erigió un monumento a la memoria en Berlín. Ceija falleció un año más tarde, en 2013, cumplidos los 80 años.

Ceija Stojka was born in 1933, meaning everything she experienced until 1945 happened during the first twelve years of her life. His overwhelming story is not the narrative of the horror experienced by a family, it is that of the entire gypsy community, the survivors and the fatal victims. It has the added value of bringing to the forefront what was ignored, what was erased as if it had not existed. It would be strange to find someone who has not heard of the Shoah, but who has heard of the Porrajmos? Thanks to her, the Austrian government has officially recognized the genocide and Angela Merkel’s government recognized in 2012 the genocide of the Roma and Sinti peoples perpetrated by the Nazi regime and erected a monument to their memory in Berlin. Ceija died a year later, in 2013, at the age of 80.

La exposición / The exhibition

Las 140 piezas de la exposición, entre escritos, dibujos y pinturas están organizadas en tres secciones: Antes y durante la caza, Los campos de exterminio y Regreso a la vida.

The 140 pieces in the exhibition, including writings, drawings and paintings, are organized into three sections: Before and during the hunt, The extermination fields and Return to life.

Antes y durante la caza / Before and during the hunt

En esta primera sección la artista refleja su vida de niña feliz, en el seno de una familia nómada dedicada al comercio de caballos, la vida idílica en el clan, la armonía con la naturaleza. Landleben (1993) es un canto a la vida campestre. Pero en Viaje en verano por los girasoles, empiezan las señales de temor aunque pretendiendo ocultarlo. Las leyes nazis del Anschluss de marzo 1938 prohibieron la vida en caravana, obligaron al sedentarismo. Fue una señal.

In this first section the artist reflects her life as a happy girl, within a nomadic family dedicated to the horse trade, the idyllic life in the clan, the harmony with nature. Landleben (1993) is a hymn to country life. But in Summer Journey through the Sunflowers, signs of fear begin, although trying to hide it. The Nazi laws of the Anschluss of March 1938 prohibited caravan life and forced a sedentary lifestyle. It was a sign.

Primero fue el arresto del padre. Ella, su madre y hermanas se escondieron en Viena hasta su arresto en marzo de 1943. La exposición recoge esta detención y todas las detenciones de romaníes, en WosindunsereRom? (¿Dónde están nuestros gitanos? Laaerberg 1938.

First was the arrest of the father. She, her mother and sisters hid in Vienna until her arrest in March 1943. The exhibition collects this arrest and all the arrests of Roma, in WosindunsereRom? (Where are our gypsies? Laaerberg 1938.

Foto Ceija Stojka: Arresto y deportación a Auschwitz

Los campos de exterminio / The extermination fields

Lo más abrumador, lo que conecta al espectador de los cuadros de la muestra con la fuerza del horror expresada en ellos, es cómo la mente de Ceija Stojka, tras más de cuatro décadas de silencio traumático, de auténtica congelación de sus recuerdos como mecanismo de defensa para sobrevivir, refleje lo vivido como si hubiera sucedido ayer. Milagrosamente el tiempo se congeló, pero no produjo olvido alguno. Sí hubo un detonante para su salida del marasmo. La tragedia de la muerte de uno de sus hijos por sobredosis.

The most overwhelming thing, what connects the viewer of the paintings in the exhibition with the force of horror expressed in them, is how Ceija Stojka’s mind, after more than four decades of traumatic silence, of authentic freezing of her memories as a defense mechanism to survive, reflects what she experienced as if it had happened yesterday. Miraculously, time froze, but it did not produce any oblivion. Yes, there was a trigger for his exit from the morass. The tragedy of the death of one of his children due to an overdose

Por mencionar uno de los cuadros dedicados a la estancia en Auschwitz, precisamente titulado Auschwitz 1944, muestra a una niña de diez años aupada sobre sus puntillas para contemplar a través de unas altísimas ventanas las chimeneas del holocausto. Unos cuervos sobrevuelan la escena, representan las almas de los muertos, pero también poder escapar tras las alambradas.

To mention one of the paintings dedicated to the stay in Auschwitz, precisely titled Auschwitz 1944, it shows a ten-year-old girl standing on her tiptoes to contemplate the Holocaust chimneys through very high windows. Some crows fly over the scene, representing the souls of the dead, but also being able to escape behind the barbed wire.

Z-6399, (Z, Zigeuner, gitana) es su número de interna marcado en su brazo, que ella pinta en una asombrosa composición abstracta. Curiosamente, desde después de la guerra no se ha vuelto a utilizar esta palabra en Alemania, ha sido sustituida por Rom o Sinti.

Z-6399, (Z, Zigeuner, gypsy) is her inmate number marked on her arm, which she paints in a stunning abstract composition. Curiously, since after the war this word has not been used again in Germany, it has been replaced by Rom or Sinti.

Ravensbrück

El ojo inyectado en sangre, sin título como otros muchos, porque así se acentúa su poder evocador, ojo siempre vigilante, es el leit motiv de la exposición. El terrible cuadro, Las mujeres de Ravensbrück, agrupadas, ondulantes, aterrorizadas, con colores violentos, es tan sobrecogedor que atrapa, cuesta trabajo apartar la vista.

The bloodshot eye, untitled like many others, because this accentuates its evocative power, an ever-watchful eye, is the leitmotif of the exhibition. The terrible painting, The Women of Ravensbrück, grouped, undulating, terrified, with violent colors, is so overwhelming that it captivates, it is difficult to look away.

Paisajes con figuras siniestras, amenazantes, como la de la vigilante Dorothea Binz. Las deportadas son apenas pinceladas fantasmales. Elementos simbólicos como las botas gigantescas de los soldados, los pájaros lúgubres, las alambradas en cuadros que respiran maldad, donde la perversidad está muy presente. ¡Stojka no había olvidado nada! Entre 1988 y 2012 se dedicó a exorcizar a sus terribles fantasmas.

Landscapes with sinister, threatening figures, like that of the vigilante Dorothea Binz. The deportees are just ghostly brushstrokes. Symbolic elements such as the soldiers’ gigantic boots, the gloomy birds, the barbed wire in paintings that breathe evil, where perversity is very present. Stojka hadn’t forgotten anything! Between 1988 and 2012 he dedicated himself to exorcising his terrible ghosts.

Bergen Belsen

Fueron pocos meses de auténtico apocalipsis, de separación familiar, de trabajos forzados, de caminar sobre cadáveres, de alimentarse de savia de plantas y raíces. Las ramas se convirtieron en su símbolo de esperanza y en la inspiración de sus obras de este periodo.

They were a few months of authentic apocalypse, of family separation, of forced labor, of walking over corpses, of feeding on plant sap and roots. The branches became his symbol of hope and the inspiration for his works of this period.

El final se refleja en Berger Belsen 1945, frente a un fondo de llamas apocalípticas pinta casi en primer plano un hermoso árbol verde, la esperanza tras el horror. El principio de la vida.

The ending is reflected in Berger Belsen 1945, in front of a background of apocalyptic flames he paints a beautiful green tree almost in the foreground, the hope after the horror. The beginning of life.

Regreso a la vida: Los girasoles

El largo camino de regreso a Viena refleja agotamiento, confusión de elementos arbóreos que tanto son Viena como Auschwitz. Recuerdo de los paisajes de antes de la guerra con cielos rosados, naranja y violeta, el pasado y el futuro se confunden. Es difícil empezar a creer en un futuro.

The long road back to Vienna reflects exhaustion, confusion of the tree elements that are both Vienna and Auschwitz. I remember the landscapes of before the war with pink, orange and violet skies, the past and the future become confused. It’s hard to start believing in the future.

Los girasoles son la flor de los romaníes y están aquí, omnipresentes, como estuvieron cuando empezó el temor, pero ahora son distintos. Hay una colección de pintura en esta sección que ella llamó pinturas de luz, donde hay estatuas de la Virgen, frutas y verduras, fé y vida recuperadas.

Sunflowers are the flower of the Roma and they are here, omnipresent, as they were when the fear began, but now they are different. There is a collection of paintings in this section that she called light paintings, where there are statues of the Virgin, fruits and vegetables, faith and life recovered.

Descubre más desde LA AGENCIA MUNDIAL DE PRENSA

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.