Picasso, His Women, His Workshops, His Life.

En una conversación reciente salió el tema de las diferencias entre el Picasso artista y el Picasso persona. O las diferencias entre un genio y un canalla. Genial como pintor, escultor, ceramista, incluso como escritor. Canalla en su comportamiento con las mujeres, al menos con las mujeres de su vida, con sus hijos, con sus empleados.

In a recent conversation, the topic came up about the differences between Picasso the artist and Picasso the person. Or the differences between a genius and a scoundrel. Brilliant as a painter, sculptor, ceramist, even as a writer. A scoundrel in his behavior toward women, at least toward the women in his life, toward his children, toward his employees.

Al hilo de esta conversación, he rescatado una reseña de mis tiempos como cronista de arte. Una, porque he de decir que de Picasso he escrito muchísimo, tanto como para integrar en un libro todos mis trabajos sobre el malagueño universal. Y quizá lo haga. He elegido rescatar esta porque precisamente habla mucho de sus dos personalidades.

Following this conversation, I’ve rescued a review from my days as an art chronicler. One, because I must say that I’ve written a great deal about Picasso, enough to compile all my works on the universal Malagueño into a book. And perhaps I will. I’ve chosen to rescue this one because it precisely talks a lot about his two personalities.

He aquí la transcripción que data de 2014.

Here is the transcription, which dates back to 2014.

“¡De nuevo Picasso! La sala X nos da la oportunidad a quienes hemos viajado para ver sus obras en museos y exposiciones, de conocer ahora lo que atesoran las colecciones privadas, –sin identificar o identificadas- la colección de su nieta Marina Picasso y algunas cesiones privadas a museos de cualquier parte del mundo.

«Picasso Again! The X gallery gives us the opportunity—for those of us who have traveled to see his works in museums and exhibitions—to now discover what private collections hold, whether unidentified or identified—the collection of his granddaughter Marina Picasso and some private loans to museums from anywhere in the world.

Siempre es un placer volver a encontrarse con antiguos conocidos, con colores primarios, líneas rectas y curvas, con gloriosos desnudos femeninos y masculinos, como en la última parte de la exposición abierta al público en esta ocasión.

It’s always a pleasure to reunite with old acquaintances, with primary colors, straight and curved lines, with glorious female and male nudes, as in the final part of the exhibition open to the public on this occasion.

Todo el mundo sabe que Picasso, desde muy joven hasta su muerte a los 91 años, estuvo casi siempre pintando su propia vida, los entornos de su vida, sus demonios personales. Que con cada relación amorosa comenzaba un nuevo ciclo de su pintura y hasta cambiaba de taller, para que todo fuera nuevo, como un nuevo comienzo, una nueva experiencia, en lo personal y en lo profesional. Que aunque prácticamente toda su carrera se desarrolló en Francia, él siempre mantuvo su nacionalidad española, aunque le ofrecieron la francesa, casi le suplicaron que la aceptase. Pero alguien nacido en Málaga, director del Museo del Prado en tiempos difíciles, que dejó un testimonio de sufrimiento del pueblo español en el Guernica, que se llamó Guernica por el bombardeo de la Luftwaffe un 27 de abril de 1937, (*) bombardeo de una ciudad española, transformada en testimonio de sufrimiento universal causado por guerras sin fin, por la interminable estupidez humana, sencillamente, no podía dejar de ser español. Ni podía dejar de ser español un apasionado por la tauromaquia, en sus múltiples versiones, desde la corrida hasta el eterno mito sagrado, tal como aparece en el Guernica, como testigo de sufrimiento secular. Ni por supuesto podía dejar de ser español alguien con su andaluza y mediterránea alegría de vivir, su sensualidad y…su mala leche. Múltiples razones para ser español a ultranza y quizá todavía me dejo alguna por ahí.

Everyone knows that Picasso, from a very young age until his death at 91, was almost always painting his own life, the surroundings of his life, his personal demons. That with each romantic relationship, a new cycle of his painting began, and he even changed workshops, so that everything would be new, like a new beginning, a new experience, both personally and professionally. That although practically his entire career developed in France, he always maintained his Spanish nationality, even though they offered him French citizenship, almost begged him to accept it. But someone born in Málaga, director of the Prado Museum in difficult times, who left a testimony of the suffering of the Spanish people in the Guernica—which was called Guernica after the Luftwaffe bombing on April 27, 1937, (*) a bombing of a Spanish city, transformed into a testimony of universal suffering caused by endless wars, by endless human stupidity—simply could not stop being Spanish. Nor could someone passionate about bullfighting, in its multiple versions, from the corrida to the eternal sacred myth, as it appears in the Guernica, as a witness to secular suffering, stop being Spanish. Nor, of course, could someone with his Andalusian and Mediterranean joie de vivre, his sensuality, and… his bad temper stop being Spanish. Multiple reasons to be Spanish to the core, and perhaps I’m still leaving some out there.

Volvamos a sus mujeres, a sus talleres. El Bateau-Lavoir y el Boulevard de Clichy para Fernande Olivier. La Rue Soelcher para Eva Gouel. La elegante Rue de la Boétie para la bailarina rusa, la bella Olga Khokhlova, su primera y cornuda esposa. Para ella y su hijo Paul los veranos en Saint Raphaël, Jean-les-Pins, Antibes o Dinard, con talleres alquilados. Para Marie Thérèse Walter y su hija Maya, el Château de Boisgeloup con su taller de escultura y producción de la Suite Vollard. Les Grands Augustins para el Guernica y Dora Maar.

Let’s return to his women, to his workshops. The Bateau-Lavoir and the Boulevard de Clichy for Fernande Olivier. The Rue Schoelcher for Eva Gouel. The elegant Rue de la Boétie for the Russian ballerina, the beautiful Olga Khokhlova, his first and cuckolded wife. For her and their son Paul, summers in Saint-Raphaël, Juan-les-Pins, Antibes, or Dinard, with rented workshops. For Marie-Thérèse Walter and their daughter Maya, the Château de Boisgeloup with its sculpture workshop and production of the Vollard Suite. Les Grands-Augustins for the Guernica and Dora Maar.

Con el fin de la guerra llega a su vida la valiente Françoise Gilot, madre de Claude y Paloma, con ellos le Château Grimaldi en Antibes, la joie de vivre, -hoy Museo Picasso – y a partir de 1948 la mansión en Vallauris. En 1953 se va Françoise, la valiente artista, que se harta de renunciar a su propio espacio vital, a su crecimiento personal, que se ahoga en el espacio Picasso, harta de su tacañería, “tenía que mantenernos a mí y a los niños”. Se va y es un golpe duro para el genio, ¿cómo se puede vivir sin Picasso? ¡No hay vida después de Picasso!, llegó a exclamar. Pero Françoise sigue demostrando a día de hoy que sí hay vida después de Picasso. En la exposición, es maravillosa la rabieta de Picasso, en toda la serie de dibujos para la revista Verve, feroces e irónicos, especialmente aquellos de La pintora y su modelo.

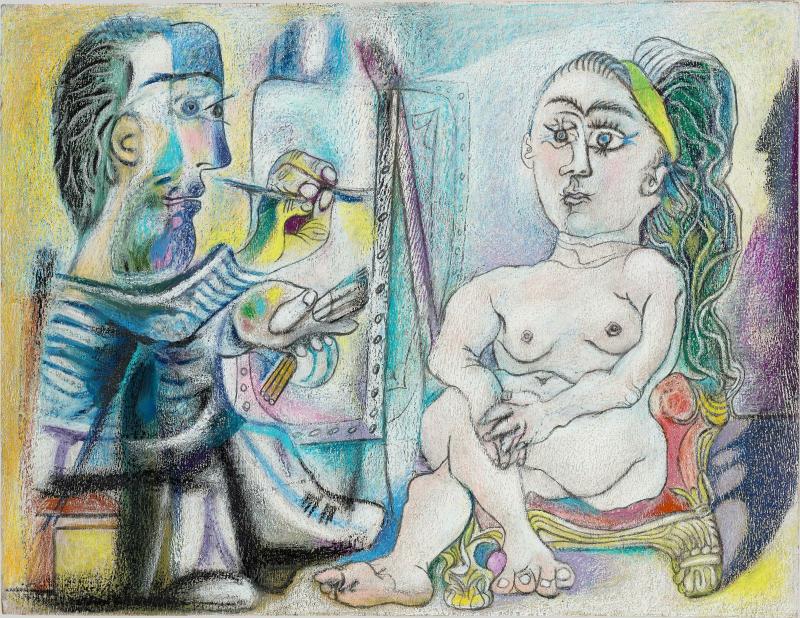

With the end of the war, the brave Françoise Gilot enters his life, mother of Claude and Paloma; with them, the Château Grimaldi in Antibes, la joie de vivre—today the Picasso Museum—and starting in 1948, the mansion in Vallauris. In 1953, Françoise leaves, the brave artist who gets tired of renouncing her own vital space, her personal growth, who suffocates in the Picasso space, tired of his stinginess, ‘he had to support me and the children.’ She leaves, and it’s a hard blow for the genius: how can one live without Picasso? ‘There’s no life after Picasso!’ he exclaimed. But Françoise continues to demonstrate to this day that there is life after Picasso. In the exhibition, Picasso’s tantrum is marvelous, in the entire series of drawings for the magazine Verve, fierce and ironic, especially those of The Painter and Her Model.

Finalmente, para la joven y sumisa Jacqueline Roque – Monseigneur le llamaba – que entra en escena en 1954, varios lugares de ensueño: La Californie en Cannes, hasta que un mal año a alguien se le ocurre construir un bloque de apartamentos que tapan las vistas al Mediterráneo. Esa villa, la Californie, que Picasso había transformado desde la cursi decoración interior belle époque, en una serie de espacios abiertos y desordenados, con talleres que invadían las estancias, creando espacios para el trabajo y los encuentros con amigos. Extraordinario testimonio fotográfico de la Californie picassiana, en la exposición. Picasso en el palomar, vista general del salón/taller, lleno de lienzos y otros materiales por doquier, Picasso conversando con su marchante Kahnweiler, Kahnweiler posando para Picasso, un Picasso relajado cortando recortables, Picasso con Jacqueline…

Finally, for the young and submissive Jacqueline Roque—whom he called Monseigneur—who enters the scene in 1954, several dream places: La Californie in Cannes, until one bad year someone decides to build an apartment block that blocks the views of the Mediterranean. That villa, La Californie, which Picasso had transformed from the tacky Belle Époque interior decoration into a series of open and disordered spaces, with workshops invading the rooms, creating spaces for work and encounters with friends. Extraordinary photographic testimony of the Picassian Californie in the exhibition. Picasso in the dovecote, general view of the living room/workshop, full of canvases and other materials everywhere, Picasso conversing with his dealer Kahnweiler, Kahnweiler posing for Picasso, a relaxed Picasso cutting out paper figures, Picasso with Jacqueline…

Los últimos talleres, esta vez sin cambiar de compañera, el Château de Vauvenargues en Provenza, al pie de la montaña Sainte Victoire, – conocida mundialmente gracias a Cézanne – y Nôtre Dame-de-Vie en Mougins. En Vauvenargues pinta la maravillosa serie El pintor y su modelo, en la que la mujer no posa, se ofrece a la manera de la Maja desnuda de Goya. En Mougins pinta la serie El pintor y la modelo distribuida entre el Museo Reina Sofía de Madrid, el Centro Pompidou de París, el Centro Galego de Arte Contemporáneo de Santiago de Compostela, el Bridgestone Museum of Art, Ishibashi Foundation, Tokio.

The last workshops, this time without changing companions: the Château de Vauvenargues in Provence, at the foot of Montagne Sainte-Victoire—known worldwide thanks to Cézanne—and Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Mougins. In Vauvenargues, he paints the marvelous series The Painter and His Model, in which the woman doesn’t pose, she offers herself in the manner of Goya’s Naked Maja. In Mougins, he paints the series The Painter and the Model, distributed between the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Galician Center for Contemporary Art in Santiago de Compostela, the Bridgestone Museum of Art, Ishibashi Foundation, Tokyo.

En Mougins pinta esas maravillas que están en colecciones particulares no identificadas: Retratos de Jacqueline, vestida y desnuda. Jacqueline con gato, pintado en cuatro sesiones, -26 y 28 de febrero y 1 y 3 de marzo de 1964. Jacqueline con sombrero amarillo y verde, otra vez Jacqueline sentada, desnuda, con las manos alzadas, la acuarela Pintor trabajando, de una intensidad indescriptible en la mirada, Pintor y modelo en un bosque, – sinfonía en verdes- y ya los varios guaches de Pintor y modelo, ambos desnudos. Esa delicia con Picasso pintando a Jacqueline, ella posando su mano en un hombro de él, muy cómplices. O Jacqueline desnuda pintando. Y los cuatro cuadros de la serie El pintor. La guinda, Hombre en un taburete, autorretrato de Picasso, que se exhibe por primera vez. Empieza la exposición con un autorretrato pintado en 1906 y termina con un autorretrato pintado en 1969, tras un recorrido vital, de intensidad única, que dura sesenta y tres años…

In Mougins, he paints those wonders that are in unidentified private collections: Portraits of Jacqueline, clothed and nude. Jacqueline with Cat, painted in four sessions—February 26 and 28, and March 1 and 3, 1964. Jacqueline with Yellow and Green Hat, again Jacqueline Seated, Nude, with Hands Raised, the watercolor Painter Working, of indescribable intensity in the gaze, Painter and Model in a Forest—a symphony in greens—and now the various gouaches of Painter and Model, both nude. That delight with Picasso painting Jacqueline, her resting her hand on his shoulder, very complicit. Or Jacqueline Nude Painting. And the four paintings from the series The Painter. The cherry on top, Man on a Stool, a self-portrait of Picasso, exhibited for the first time. The exhibition begins with a self-portrait painted in 1906 and ends with a self-portrait painted in 1969, after a vital journey of unique intensity that lasts sixty-three years…

En cada ciclo, aparecen retratos de sus mujeres: Fernande, – Eva – Olga y Paul, varios de Marie Thérèse, de Dora, de Françoise, los innumerables de Jacqueline. Luces y sombras del universo Picasso, de las sombras que supo librarse Françoise, y en cierto modo Marie Thérèse, que se mantuvo ahí, separada y humillada, pero siempre volviendo a verle de forma intermitente, termina sus días ahorcada. Maya conserva buenos y malos recuerdos de su padre. Fernande murió pobre y olvidada. ¡No hay vida después de Picasso! Olga, que le negó el divorcio hasta su muerte, sumida en la locura, igual que Paul, ¡aquel delicioso niño arlequín! del Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza, humillado por su padre desde la infancia, hasta el punto de contratarle como chófer, murió alcoholizado. Pablito, el hijo de Paul y hermano de Marina, se suicidó a los dos días de la muerte del abuelo. Dora enloqueció y Jacqueline…que podía haber vivido libre y millonaria tras la muerte de Picasso, acabó pegándose un tiro, ¿por un desamor?. ¡No hay vida después de Picasso! El gran genio creador de obras de arte y gran destructor de su familia.

In each cycle, portraits of his women appear: Fernande—Eva—Olga and Paul, several of Marie-Thérèse, of Dora, of Françoise, the innumerable ones of Jacqueline. Lights and shadows of the Picasso universe, from the shadows that Françoise managed to free herself from, and in a certain way Marie-Thérèse, who stayed there, separated and humiliated, but always returning to see him intermittently, ends her days by hanging herself. Maya keeps good and bad memories of her father. Fernande died poor and forgotten. ‘There’s no life after Picasso!’ Olga, who denied him a divorce until her death, sunk into madness, just like Paul—that delightful harlequin child! from the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum—humiliated by his father since childhood, to the point of hiring him as a chauffeur, died an alcoholic. Pablito, Paul’s son and Marina’s brother, committed suicide two days after his grandfather’s death. Dora went mad, and Jacqueline… who could have lived free and a millionaire after Picasso’s death, ended up shooting herself, due to heartbreak? ‘There’s no life after Picasso!’ The great genius creator of works of art and great destroyer of his family.

¡Qué largo ha sido el siglo XX! Una revolución rusa, dos guerras mundiales, una guerra civil, una dictadura que le aleja de su amada España. Pintura azul y rosa, cubismo cezanniano, analítico, sintético, clasicismo y naturalismo con toques cubistas, surrealismo a la manera de Picasso, y después él es sus propios ismos. Los talleres como espacios del alma, laboratorios de arte y vida, mi paisaje interior. – dixit– Se despide del cubismo en 1914, con hombre en un sillón. Supera el cubismo vía clasicismo de vanguardia entre 1917 y 1920. Resplandece el colorido y la luz mediterránea en Bodegón delante de un balcón y Velador delante de un balcón. 1920 al 27, los espacios no son lugares vacíos, son parte al igual que los volúmenes de lo que existe, cuadro o naturaleza, como esa pequeña escultura de papel recortado Guitarra y mesa delante de una ventana. Bodegones con guitarras, mandolinas, vasos, fruteros, veladores, una Naturaleza muerta con busto, Cuerpo con paleta, caballete y jarra, Guitarra y frutero con naranjas-clasicismo más naturalismo, con mucho color y matices, donde las rectas van cediendo a las curvas. Es una época de transición, de volver a reencontrarse, época de bodegones.

How long the 20th century has been! A Russian Revolution, two world wars, a civil war, a dictatorship that keeps him away from his beloved Spain. Blue and rose painting, Cézannian cubism, analytical, synthetic, classicism and naturalism with cubist touches, surrealism in the Picasso manner, and afterward he is his own isms. The workshops as spaces of the soul, laboratories of art and life, my inner landscape—dixit. He bids farewell to cubism in 1914, with Man in an Armchair. He surpasses cubism via avant-garde classicism between 1917 and 1920. The color and Mediterranean light shine in Still Life in Front of a Balcony and Sideboard in Front of a Balcony. From 1920 to ’27, spaces are not empty places; they are part, just like the volumes of what exists, painting or nature, like that small sculpture of cut paper Guitar and Table in Front of a Window. Still lifes with guitars, mandolins, glasses, fruit bowls, sideboards, a Still Life with Bust, Body with Palette, Easel and Jug, Guitar and Fruit Bowl with Oranges—classicism plus naturalism, with lots of color and nuances, where straight lines give way to curves. It’s a period of transition, of rediscovering himself, a period of still lifes.

El pintor y la modelo irrumpe con la fuerza de la juventud de Marie Thérèse desde 1927. Ha nacido un nuevo género. Pintor en su taller, Mujer tendida al sol, bajo una lámpara, Durmiente bajo un árbol, vestida de rojo…-exaltación de los atributos femeninos- Años 30. Marie Thérèse, Boisgeloup, escultura, suite Vollard…Minotauro, surrealismo, la guerra, Dora Maar, Grands Augustins, el Guernica…Visitado en su estudio por el embajador alemán en París, éste le pregunta ante el Guernica: ¿Esto lo ha hecho usted? No, -responde Picasso- Esto lo han hecho ustedes. Retratos de Dora en sillón rojo, sentada con abecedario, recostada…

The Painter and the Model bursts in with the force of Marie-Thérèse’s youth from 1927. A new genre is born. Painter in His Workshop, Woman Lying in the Sun, Under a Lamp, Sleeping Under a Tree, dressed in red…—exaltation of feminine attributes—1930s. Marie-Thérèse, Boisgeloup, sculpture, Vollard Suite… Minotaur, surrealism, the war, Dora Maar, Grands-Augustins, the Guernica… Visited in his studio by the German ambassador in Paris, who asks him in front of the Guernica: ‘Did you do this?’ No, Picasso responds—’You did this.’ Portraits of Dora in a red armchair, seated with alphabet, reclining…

Hay naturalezas muertas con cráneos para describir el estado de ánimo en la guerra mundial, pero quizá es el cuadro Ventana del taller, un interior con ventana que se asoma a un paisaje de tejados de París. En el interior, un radiador y tubería que desciende por la pared, sin calor, imagen de la penuria de la guerra, ausencia de figuras, el más impactante.

There are still lifes with skulls to describe the mood during the world war, but perhaps the painting Window of the Workshop, an interior with a window overlooking a landscape of Paris rooftops. Inside, a radiator and pipe descending the wall, without heat, image of wartime hardship, absence of figures, is the most impactful.

Con el fin de la guerra llega a su vida Françoise, una nueva modelo para el pintor, la alegría de vivir recuperada, vida en el Mediterráneo, en el château Grimaldi de Antibes, cuatro meses de pintura alegre, con colores cálidos. 1947 y 48 traen a Claude y Paloma, se trasladan a Vallauris, viven felices, pero la relación se va deteriorando y en 1953 Françoise dice adiós.

With the end of the war, Françoise enters his life, a new model for the painter, joie de vivre recovered, life in the Mediterranean, in the Château Grimaldi in Antibes, four months of joyful painting, with warm colors. 1947 and ’48 bring Claude and Paloma, they move to Vallauris, they live happily, but the relationship deteriorates, and in 1953 Françoise says goodbye.

La recta final de su vida con Jacqueline, es una etapa de enorme producción pictórica, escultórica, cerámica, intensamente vital y social, ahí están los Dominguín, los grupos de flamenco, las corridas de toros, la vida como empezó, bajo el sol brillante del Mediterráneo, con los cuerpos gloriosos…Luces y sombras quizá del mayor genio del siglo XX.”

The final stretch of his life with Jacqueline is a stage of enormous pictorial, sculptural, ceramic production, intensely vital and social; there are the Dominguíns, the flamenco groups, the bullfights, life as it began, under the bright Mediterranean sun, with glorious bodies… Lights and shadows perhaps of the greatest genius of the 20th century.»

(*) El Presidente alemán, Frank Walter Steinmeyer pide perdón en Guernica por el bombardeo de la Luftwaffe el 26 de abril de 1937, el pasado viernes 28 de noviembre 2025, depositando una ofrenda floral por las víctimas en presencia del rey Felipe VI.

(*) The German President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, asks for forgiveness in Guernica for the Luftwaffe bombing on April 26, 1937, last Friday, November 28, 2025, by laying a floral offering for the victims in the presence of King Felipe VI.

Nunca es tarde…

It’s never too late…

Descubre más desde LA AGENCIA MUNDIAL DE PRENSA

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.