TERESA FERNANDEZ HERRERA. Periodista, Escritora, Editorialista. CDG de CULTURA. COLUMNISTA

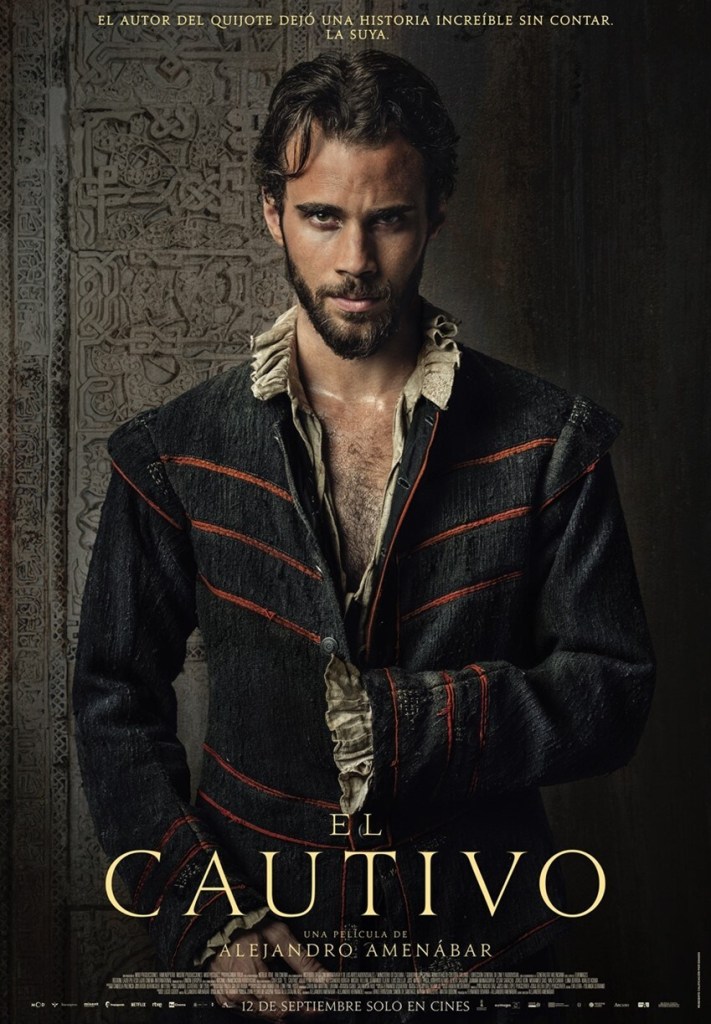

Al hilo del último estreno de Alejandro Amenábar “El Cautivo” en cines de toda España el 12 de septiembre, y sin intención de hacer una reseña al uso de la película, ésta me ha proporcionado material para adentrarme en una de las ciudades portuarias más importantes del Mar Mediterráneo a mediados del siglo XVI, tanto desde un punto de vista comercial, poblacional, cosmopolita y actividad corsaria de aquel entonces.

Following the latest release of Alejandro Amenábar’s film «El Cautivo» in cinemas throughout Spain on September 12, and without any intention of making a review of the film, this has provided me with material to delve into one of the most important port cities of the Mediterranean Sea in the mid-16th century, from a commercial, population, cosmopolitan and corsair activity point of view at that time.

En 1575, Argel era quizá el segundo puerto más importante del Imperio Otomano, después de Estambul y su cabeza de puente en el Mediterráneo. Era una ciudad bulliciosa, con gran actividad. Su diversidad racial pasaba por además de la población local, turcos, berberiscos de todo el Magreb, moriscos musulmanes de origen español y cautivos cristianos, algunos afortunados rescatables y la mayoría sin esperanza de salir de una situación de esclavitud. Todos convivían en los llamados Baños de Argel, en términos de hoy, prisiones, en condiciones muy duras. Además había siempre temor a que España después de la victoria de Lepanto, repitiera con mejor planificación y resultado el intento de conquista fallido de 1541, en tiempos de Carlos V. Esto empeoraba si cabe la situación de los cautivos.

In 1575, Algiers was perhaps the second most important port in the Ottoman Empire, after Istanbul and its Mediterranean bridgehead. It was a bustling city, teeming with activity. Its racial diversity included, in addition to the local population, Turks, Berbers from across the Maghreb, Muslim Moriscos of Spanish origin, and Christian captives, some fortunate enough to be rescued and most with no hope of escaping slavery. They all lived together in the so-called Baths of Algiers, in today’s terms called prisons, in very harsh conditions. Furthermore, there was always fear that Spain, after the victory at Lepanto, would repeat, with better planning and success, the failed attempt at conquest of 1541 under Charles V. This made the captives’ situation even worse.

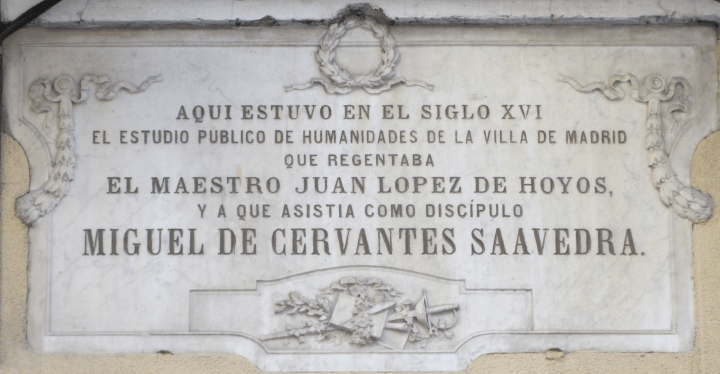

Un joven soldado Miguel de Cervantes de veinticuatro años, después de pasar algún tiempo en Italia, participó en la batalla de Lepanto en 1571, en aquella flota victoriosa comandada por Don Juan de Austria, hermanastro del rey Felipe II. Un jovencísimo Miguel que antes de enrolarse en el ejército para escapar de un desdichado incidente con armas de por medio, ya había apuntado maneras como escritor. Por desgracia para él, en Lepanto un tiro de arcabuz le “estropeó” la mano izquierda, perdiendo su movilidad, pero aún continuó su carrera en las armas y participó en la reconquista de Túnez y Orán en 1574. En 1575 cuando regresaba a España, con cartas de recomendación de Don Juan de Austria que le facilitaran un cargo público, su barco, la galera Sol, ya en aguas catalanas fue apresado por corsarios berberiscos que lo llevaron a él, su hermano Rodrigo y más de cien hombres más a Argel. Precisamente esas cartas de recomendación le convirtieron en cautivo rescatable a un altísimo precio para entonces: Quinientos escudos. Lo normal eran cien o ciento cincuenta. Era difícil reunirlos, por eso su cautiverio duró cinco años, hasta 1580.

A young soldier Miguel de Cervantes aged twenty-four, after spending some time in Italy, participated in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, in that victorious fleet commanded by Don Juan of Austria, half-brother of King Philip II. A very young Miguel who before enlisting in the army to escape an unfortunate incident involving weapons, had already shown promise as a writer. Unfortunately for him, at Lepanto an arquebus shot “ruined” his left hand, losing its mobility, but he still continued his military career and participated in the reconquest of Tunis and Oran in 1574. In 1575 when he was returning to Spain, with letters of recommendation from Don Juan of Austria that would facilitate a public office, his ship, the galley Sol, already in Catalan waters was captured by Barbary corsairs who took him, his brother Rodrigo and more than a hundred other men to Algiers. It was precisely those letters of recommendation that made him a ransomable captive at a very high price at the time: 500 escudos. The usual price was 100 or 150. It was difficult to gather them, so his captivity lasted five years, until 1580.

Se diría que cinco años son poca cosa en la vida de un hombre que vivió sesenta y ocho y que murió famoso internacionalmente. Sin embargo, fueron cinco años cruciales en su maduración como hombre, en su adquisición de fortaleza para sobrevivir a una terrible adversidad, y sin duda como futuro escritor.

It might seem that five years are not much in the life of a man who lived to be sixty-eight and died internationally famous. However, they were five crucial years in his maturation as a man, in acquiring the strength to survive terrible adversity, and undoubtedly as a future writer.

Esos cinco años son los que Amenábar ha relatado en “El Cautivo”, que ha levantado no poca polémica por algo en lo que entraré después. Ha dicho Amenábar que Cervantes escribió muchas historias sobre Argel menos la suya. Sí y no. No su historia entera, pero si muchos datos biográficos tanto en el Quijote, en su relato “El cautivo”, como en otras obras, “Los tratos de Argel”, “El gallardo español” y “La gran Sultana”. Como también le influenció Italia. En el Quijote está la deliciosa historia de “El curioso impertinente”. Sin estas experiencias Cervantes no hubiera sido el escritor que fue.

Those five years are what Amenábar recounted in “The Captive,” which has sparked no small amount of controversy for reasons I’ll get into later. Amenábar has said that Cervantes wrote many stories about Algiers, except for his own. Yes and no. Not the entire story, but plenty of biographical details, both in Don Quixote, with his story “The Captive,” and in other works, “The Dealings of Algiers,” “The Gallant Spaniard,” and “The Great Sultana.” He was also influenced by Italy. Don Quixote contains the delightful story of “The Impertinent Curious Man.” Without these experiences, Cervantes would not have been the writer he was.

Amenábar, como centenares de literatos y cineastas que han llevado personajes históricos a la novela o al cine, (o a ambos) mezcla la historia con la ficción. Por ejemplo, el Padre Sosa, fue un Padre Sousa, portugués que llegó cautivo a Argel en 1577, dos años después que Cervantes. Pero el Padre Blanco de la película, aunque verosímil , yo diría que incluso necesario, es un personaje de ficción. Una de las cosas más complicadas de reproducir en esta clase de obras, es la ambientación. En los primeros cinco minutos de “El Cautivo”, Argel se muestra en todo su esplendor, con su bullicio, su diversidad étnica, su importancia comercial con la visión de la actividad del puerto.

Amenábar, like hundreds of writers and filmmakers who have brought historical figures to novels or films (or both), blends history with fiction. For example, Father Sosa, a Portuguese man who arrived as a captive in Algiers in 1577, two years after Cervantes. But the film’s Father Blanco, although historically plausible—I would say even necessary—is a fictional character. One of the most difficult things to capture in this kind of work is the setting. In the first five minutes of «The Captive,» Algiers is shown in all its splendor, with its bustle, its ethnic diversity, its commercial importance, and the glimpse of the port’s activity.

Ya he dicho al principio que no me interesa hacer una reseña de la película, pero sí me permito recomendarla, por su excelente manufactura, su verosimilitud histórica y por las preguntas que plantea a las cuales cada espectador tendrá que dar respuesta.

I already said at the beginning that I’m not interested in reviewing the film, but I do recommend it for its excellent craftsmanship, its historical verisimilitude, and the questions it raises that every viewer will have to answer.

El segundo apellido de Cervantes en Argel era Cortina, heredado de su madre doña Leonor Cortina. ¿De dónde sale el segundo apellido Saavedra que utilizará Cervantes en su vida como escritor y con el que ha pasado a la historia? Investiguen.

Cervantes’s second surname in Algiers was Cortina, inherited from his mother, Doña Leonor Cortina. Where does the second surname, Saavedra, come from, which Cervantes used throughout his life as a writer and with which he has gone down in history? Do some research.

Cervantes capitaneó cuatro intentos de fuga, todos fallidos. Se sabe que en Argel el castigo era corte de una oreja o nariz o mano a los secundarios, empalamiento a los promotores de los intentos de fuga. En la película presenciamos el corte de una oreja, no recuerdo si a un secuaz de Cervantes o no, eso carece de importancia. ¿Porqué a Miguel de Cervantes, promotor de cuatro intentos de fuga, nunca se le cortó nada, aunque sí se le castigó con endurecimiento de las condiciones de su cautiverio, privándole de su relativa libertad para moverse por Argel? ¿Por su condición de rescatable por mucho dinero como por fin sabemos que sucedió? ¿O por otra causa?

Cervantes led four escape attempts, all of which failed. It is known that in Algiers, the punishment was the cutting off of an ear, nose, or hand for secondary figures, and the impalement of those instigating escape attempts. In the film, we witness the cutting off of an ear; I don’t remember whether it belonged to a Cervantes henchman or not; that’s irrelevant. Why was Miguel de Cervantes, the instigator of four escape attempts, never cut off, although he was punished by harsher conditions of his captivity, depriving him of his relative freedom to move around Algiers? Was it because he could be redeemed for a lot of money, as we finally learn happened? Or for another reason?

Es cierto que su capacidad para inventar y narrar historias le hizo adquirir notoriedad entre sus compañeros de cautiverio. A ellos los distraía y hacía olvidar por un rato su triste condición de presos, prácticamente esclavos, que pasaban hambre y sufrían torturas en cuanto se descuidaban. La mayoría no sobrevivía mucho tiempo en cautiverio, los que no valían nada, los que no podían esperar rescate, salían caros a sus amos.

It’s true that his ability to invent and tell stories made him famous among his fellow prisoners. He distracted them and made them forget for a while their sad condition as prisoners, practically slaves, who suffered hunger and torture whenever they were careless. Most didn’t survive long in captivity; those who were worthless, those who couldn’t expect ransom, cost their masters dearly.

La pregunta crucial: ¿Tuvo el joven Cervantes, una relación sentimental nada menos que con el Bajá Hassan, máxima autoridad política de Argel? En la película, sí. Pero, ¿es historia o ficción?

The crucial question: Did the young Cervantes have a romantic relationship with none other than Pasha Hassan, the highest political authority in Algiers? In the film, yes. But is it history or fiction?

No voy a entrar en la polémica y hasta críticas por esta parte del relato en “El Cautivo”. Amenábar tiene todo el derecho del mundo a ficcionar o historiar algo que pudo o no pudo ser y que sin duda añade morbo a lo que cuenta, muy bien contado, por cierto.

I’m not going to enter into the controversy and even criticism surrounding this part of the story in «The Captive.» Amenábar has every right in the world to fictionalize or chronicle something that could or could not have been, and that undoubtedly adds morbidity to what he tells, very well told, by the way.

¿Qué hacer con esta pregunta? Es un hecho que en la sociedad musulmana de Argel la homosexualidad se castigaba con la sharia. A nivel particular, según quién y cómo podía tolerarse. En las sociedades cristianas de la época, era el pecado nefando. El sexo estaba para procrear, no para disfrutar, aunque muy privadamente se disfrutaba.

What should we do with this question? It is a fact that in the Muslim society of Algiers, homosexuality was punished under Sharia law. On an individual level, depending on who and how it could be tolerated. In the Christian societies of the time, it was a heinous sin. Sex was for procreation, not for enjoyment, although it was enjoyed very privately.

No consta que Cervantes en España mostrara jamás una tendencia ni siquiera bisexual, suponiendo, que es mucho suponer, que existiera ese término hace cinco siglos. Lo dudo. Es bien conocida la historia de su matrimonio de conveniencia, como casi todos los de entonces, y de su historia de amor extramatrimonial.

There’s no evidence that Cervantes ever displayed even bisexual tendencies in Spain, assuming—and it’s a long assumption—that the term existed five centuries ago. I doubt it. The story of his marriage of convenience, like almost all those of that time, and his extramarital love affair are well known.

Volviendo a la película. Cuando llegan al puerto de Argel el barco y el dinero de su rescate, no recuerdo bien quién, quizá el ficticio Padre Blanco, o el Padre Sosa o Sousa le pregunta: “¿Quieres regresar?”

Back to the film. When the ship and the ransom money arrive at the port of Algiers, I don’t quite remember who, perhaps the fictional Father Blanco, or Father Sosa, or Sousa, asks him: «Do you want to go back?»

Uno, dos, tres segundos de espera y luego, “¡Sí, quiero regresar!, ¡¡Sí, quiero regresar!!, ¡¡¡Sí, quiero regresar!!!»

One, two, three seconds of waiting, and then, «Yes, I want to go back!» and he repeats it three or more times.

Esto ya podría ser una respuesta. Pero, ¿a qué pregunta?

This could already be an answer. But to what question?

No he leído que nadie haya dicho lo que voy a decir aquí, que pudo ser posible y muy verosímil.

I haven’t read that anyone has said what I’m about to say here, that it could have been possible and very plausible.

La historia ha demostrado centenares, miles de veces, que cuando una persona se encuentra en una situación límite, con tal de sobrevivir, hace lo que sea, aunque sea lo más contrario a su naturaleza.

History has shown hundreds, thousands of times, that when a person finds themselves in a dire situation, in order to survive, they will do anything, even if it’s the most contrary to their nature.

Ser cautivo cristiano en Argel era sin duda una situación límite. Y si una persona poderosa se fijaba en alguien, hombre o mujer, la repuesta era, someterse o morir.

Being a Christian captive in Algiers was undoubtedly a difficult situation. And if a powerful person set their sights on someone, man or woman, the answer was either submit or die.

Cada uno, si así lo desea, que se haga esta u otra pregunta.

Each of you, if you wish, can ask yourself this or another question.

Pero no dejen de ver “El Cautivo”. Por cierto, el joven actor de veinticinco años, Julio Peña, borda el papel del joven Miguel de Cervantes y Cortina.

But don’t miss «El Cautivo.» By the way, the young twenty-five-year-old actor, Julio Peña, perfectly plays the role of the young Miguel de Cervantes y Cortina.

Descubre más desde LA AGENCIA MUNDIAL DE PRENSA

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.