Portmán Bay, a story that should never have happened

COLUMNISTA

El pasado domingo 10 de agosto quise ver en vivo y en directo las consecuencias de una historia de tres décadas de vertidos de residuos mineros sobre una bahía, Portmán, el romano Portus Magnus, que durante siglos de historia había sido un referente medioambiental europeo de flora y fauna marina, a cuyo alrededor había ido creciendo el pueblo de Portmán, rodeado de la sierra minera que abarca el Campo de Cartagena – La Unión, desde la fundación de esta última ciudad en 1868. Portmán es una pedanía de La Unión.

Last Sunday, August 10, I wanted to see live and direct the consequences of a three-decade history of dumping mining waste into a bay, Portmán, the Roman Portus Magnus, which for centuries of history had been a European environmental benchmark for marine flora and fauna, around which the town of Portmán had grown, surrounded by the mining mountain range that encompasses Campo de Cartagena – La Unión, since the founding of the latter city in 1868. Portmán is a hamlet of La Unión.

Tuve el enorme privilegio de estar acompañada en esta visita por el Alcalde pedáneo de Portmán, Ginés Ortiz, concertada por medio de la Concejala de Cultura de La Unión, Aurora Ródenas, a quién había expresado mi deseo de escribir un gran reportaje que diese cobertura a estos hechos que constituyen uno de los mayores desastres medioambientales en el Mediterráneo, provocado por la acción humana.

I had the enormous privilege of being accompanied on this visit by the Mayor of Portmán, Ginés Ortiz, arranged through the Councilor for Culture of La Unión, Aurora Ródenas, to whom I had expressed my desire to write a major report covering these events, which constitute one of the greatest environmental disasters in the Mediterranean, caused by human action.

Mis alertas llegaron a través de las redes sociales del alcalde de La Unión, Joaquín Zapata, y su activismo en contra de la última decisión del Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica de renunciar a las acciones de dragado, descontaminación y recuperación de la bahía consensuadas en 2006 con el gobierno de José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero y sustituirlas por un “sellado” avalado por el Centro de Estudios y Experimentación de Obras Públicas. (CEDEX), sin que haya mediado conversación ni consenso alguno. Sellado, cubrir la bahía cegada por el vertido de más de 60.000.000 de toneladas de residuos altamente tóxicos, que seguirían ahí ad aeternum bajo el “sellado” o enterramiento. En palabras de Ginés Ortiz, la muerte de Portmán.

My alerts came through the social networks of the mayor of La Unión, Joaquín Zapata, and his activism against the latest decision by the Ministry for Ecological Transition to abandon the dredging, decontamination and recovery actions of the bay agreed upon in 2006 with the government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and replace them with a «sealing» endorsed by the Center for Studies and Experimentation of Public Works (CEDEX), without any discussion or consensus. Sealing, covering the bay blinded by the dumping of more than 60,000,000 tons of highly toxic waste, which would remain there ad aeternum under the «sealing» or burial. In the words of Ginés Ortiz, the death of Portmán.

En 1957, la empresa francesa Société Minière et Métallurgique, en España Sociedad Minera y Metalúrgica Peñarroya S.A., (SMMP-E) obtuvo concesiones oficiales en esta sierra minera y se centró en la extracción intensiva a cielo abierto, (una metodología declarada ilegal mundialmente desde hace años) de diversos minerales, y su proceso de separación de metales y residuos estériles en el Lavadero Roberto. Desde ahí los residuos de zinc, cadmio, plomo y restos reactivos, fueron arrojados sistemáticamente a la Bahía de Portmán, (1957- 1990) con la consiguiente alteración morfológica y contaminación del ambiente marino. Esto a pesar de que las concesiones hechas y renovadas por las administraciones de turno estaban condicionadas a “no causar perjuicio ni merma alguna en la bahía”.

In 1957, the French company Société Minière et Métallurgique, in Spain Sociedad Minera y Metalúrgica Peñarroya S.A., (SMMP-E) obtained official concessions in this mining mountain range and focused on intensive open-pit extraction (a methodology declared illegal worldwide years ago) of various minerals, and its process of separation of metals and sterile waste in the Lavadero Roberto. From there, the zinc, cadmium, lead and reactive remains were systematically dumped into the Bay of Portmán, (1957-1990) with the consequent morphological alteration and contamination of the marine environment. This was despite the fact that the concessions made and renewed by the administrations in power were conditioned on «not causing any harm or loss to the bay.»

He escuchado reiteradamente que esto fue posible gracias al franquismo. En principio es cierto. Pero la dictadura terminó en 1975; es comprensible que en el periodo constituyente no cambiara nada, pero en 1977 hubo unas elecciones democráticas con un gobierno de centro derecha y desde 1982 hasta 1998 hubo gobiernos socialistas con mayoría absoluta, pero Portmán siguió olvidado. La recién nacida Comunidad de Murcia también estuvo presidida durante esos años críticos por gobiernos del PSOE. En cuanto al Ayuntamiento de La Unión como todo el sistema municipal de España estuvo involucrado por aquellos años en una transición democrática.

I’ve heard repeatedly that this was possible thanks to Franco’s regime. In principle, that’s true. But the dictatorship ended in 1975; it’s understandable that nothing changed during the constituent period, but in 1977 there were democratic elections with a center-right government, and from 1982 to 1998 there were socialist governments with an absolute majority, but Portmán remained forgotten. The newly formed Community of Murcia was also presided over during those critical years by PSOE governments. As for the City Council of La Unión, like the entire municipal system in Spain, it was involved in a democratic transition during those years.

A partir de 1957 fueron años de enorme producción con la consiguiente generación de puestos de trabajo. Hablamos de años en que no existía una conciencia medioambiental; que la acción de Peñarroya S.A. era la típica de un capitalismo despiadado donde lo único que importaba eran enormes beneficios a corto plazo, sin que las consecuencias importaran lo más mínimo.

From 1957 onward, there were years of enormous production, with the resulting job creation. These were years in which environmental awareness was lacking; Peñarroya S.A.’s actions were typical of a ruthless capitalism where the only thing that mattered was huge short-term profits, with no regard for the consequences.

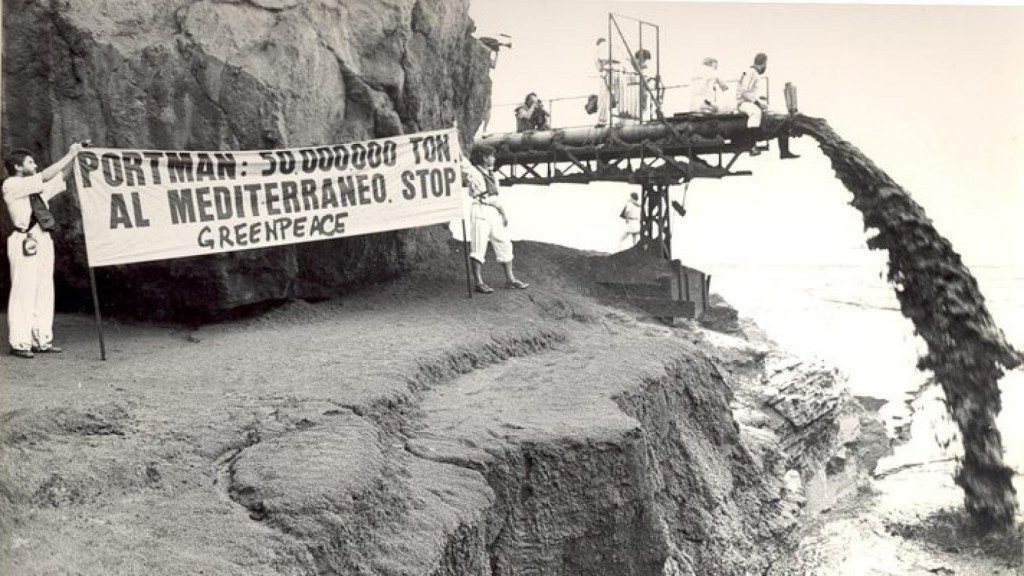

Greenpeace, la primera alarma, 31 de julio 1986. Greenpeace, the first alarm, July 31, 1986.

Un grupo de seis activistas de Greenpeace, liderados por la viguesa Teresa Pérez, fueron fotografiados por Lorette Dorreboom en el intento de taponar la tubería que expulsaba los estériles. “Llegamos muy temprano, atravesamos el mar de fango que cubría la playa e intentamos taponar la tubería de los vertidos. Vivimos momentos peligrosos, incluso llegamos a temer por nuestra integridad física. Mientras dos compañeros intentaban taponar el tubo, otros dos a pie de playa exhibieron pancartas y Zoa y Teresa, las dos restantes se encadenaron a la puerta para impedir el paso de trabajadores”.

A group of six Greenpeace activists, led by Teresa Pérez from Vigo, were photographed by Lorette Dorreboom attempting to plug the pipe discharging tailings. “We arrived very early, crossed the sea of mud covering the beach, and tried to plug the waste pipe. We experienced dangerous moments, even fearing for our physical safety. While two colleagues tried to plug the pipe, two others on the beach displayed banners, and Zoa and Teresa, the remaining two, chained themselves to the gate to prevent workers from entering.”

Ante esto, la empresa aumentó la presión para impedir el taponado, convirtiendo el vertido en un aspersor, haciendo temblar la plataforma con riesgo de romperse. A esto se sumaron los trabajadores mineros que trataron de detener a las activistas con acciones agresivas. La guardia civil puso fin a toda la acción, las activistas acabaron en el cuartelillo donde las obligaron a ducharse porque el fango que las cubría se desparramaba por todas partes…

In response, the company increased pressure to prevent the capping, turning the spill into a sprinkler, causing the platform to shake and risk breaking. Added to this were the miners, who tried to stop the activists with aggressive actions. The Civil Guard put an end to the entire action; the activists ended up in the barracks, where they were forced to shower because the mud covering them was spilling everywhere…

La foto de las activistas encadenadas dio la vuelta al mundo y fue el punto de inflexión para que cuatro años más tarde cesaran los vertidos y se intensificaran las protestas, como la llevada a cabo frente al Ministerio de Medio Ambiente en 1987 que incluyó un vertido de lodo de Portmán. Estos hechos resultaron en el documental “Portmán, un punto y seguido”, exhibido recientemente en el Senado el 4 de marzo 2024, en presencia del alcalde de La Unión, Joaquín Zapata, Presidente del Senado Pedro Rollán, Consejero de Medioambiente, Universidades, Investigación y Mar Menor, diseñadores del documental, la fotógrafa Lorette Dorreboom, invitados, etc.

The photo of the chained activists went around the world and was the turning point for the dumping to stop four years later and the protests to intensify, such as the one carried out in front of the Ministry of the Environment in 1987 which included a spill of Portmán mud. These events resulted in the documentary “Portmán, a point and followed”, recently exhibited in the Senate on March 4, 2024, in the presence of the mayor of La Unión, Joaquín Zapata, President of the Senate Pedro Rollán, Minister of the Environment, Universities, Research and Mar Menor, designers of the documentary, photographer Lorette Dorreboom, guests, etc.

Peñarroya España S.A. desapareció, vendiendo todos sus activos en 1991 a la Sociedad Portmán Golf, S.A., cuyos propietarios son los empresarios cartageneros Alfonso García y Mariano Roca, también propietarios de gran parte de los terrenos de la Sierra Minera. En 2020 cedieron la gestión de la empresa a dos profesionales independientes, Juan Carlos García y José Vicente Albaladejo. Hasta la fecha ninguna de estas empresas se ha responsabilizado de ningún pago, ni a los 350 trabajadores despedidos ni por los ingentes perjuicios contaminantes y desaparición de la bahía. El convenio de descontaminación y recuperación de 2006 firmado por el gobierno Zapatero se paralizó en 2018, tras algún intento de intervención en 2016. En realidad, nada, no se ha hecho nada.

Peñarroya España S.A. disappeared, selling all its assets in 1991 to Sociedad Portmán Golf, S.A., owned by Cartagena businessmen Alfonso García and Mariano Roca, who also owned a large portion of the land in the Sierra Minera. In 2020, they transferred management of the company to two independent professionals, Juan Carlos García and José Vicente Albaladejo. To date, neither of these companies has accepted any payment, neither to the 350 laid-off workers nor for the massive pollution damage and the disappearance of the bay. The 2006 decontamination and recovery agreement signed by the Zapatero government was paralyzed in 2018, following an attempted intervention in 2016. In reality, nothing, nothing, has been done.

Ahora, ante la última decisión del Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica (MITECO) avalado por un estudio del CEDEX, tras valorar varias alternativas , ve como intervención más viable el sellado de la desaparecida bahía, cegada por los 60 millones de toneladas de metales tóxicos vertidos a lo largo de más de tres décadas.

Now, in light of the latest decision by the Ministry for Ecological Transition (MITECO), supported by a CEDEX study, after evaluating several alternatives, it sees the sealing of the vanished bay, clogged by the 60 million tons of toxic metals dumped over more than three decades, as the most viable intervention.

El CEDEX no ve viable el dragado de los residuos mineros soterrados, porque podrían liberar metales pesados – plomo, zinc, cadmio o arsénico- que se vuelven solubles y pueden entrar en suspensión al ser removidos, contaminando mayor extensión de entorno marino. En resumen, según el CEDEX el dragado no es una opción segura, debido a los riesgos ambientales que produciría la liberación de metales pesados.

CEDEX does not consider dredging the buried mining waste viable because it could release heavy metals—lead, zinc, cadmium, or arsenic—which become soluble and can enter suspension when removed, contaminating a larger area of the marine environment. In short, according to CEDEX, dredging is not a safe option due to the environmental risks that the release of heavy metals would pose.

Esto sería reconocer que el acuerdo de 2006 fue todo menos científicamente viable, por eso quizá nunca se hizo nada. Pero mantuvo durante años la ilusión de regeneración y recuperación de la bahía anterior a las acciones de Peñarroya S.A. en los habitantes de la zona. Eso hace comprensible la discrepancia con el sellado por parte de la Fundación Sierra Minera, el Ayuntamiento de La Unión y de la Comunidad Autónoma de Murcia. Para ellos, que siempre han estado ahí, el sellado certifica la sentencia de muerte de Portmán.

This would be an acknowledgment that the 2006 agreement was anything but scientifically viable, which is perhaps why nothing was ever done. But it maintained for years the hope of regeneration and recovery of the bay among the inhabitants of the area prior to the actions of Peñarroya S.A. This makes the discrepancy with the seal issued by the Sierra Minera Foundation, the City Council of La Unión, and the Autonomous Community of Murcia understandable. For them, who have always been there, the seal certifies Portmán’s death sentence.

Sin ánimo de opinar, carezco de formación científica para permitirme tal cosa, creo que dada toda la terrible historia que jamás debió ocurrir, la mayor catástrofe medioambiental del Mediterráneo causada por intervención humana, sin que jamás haya habido responsabilidades por este hecho, algo también incomprensible, creo que tendría sentido que un Centro de Estudios independiente y neutral, preferiblemente no español, hiciese otra valoración de las opciones que se han manejado, dragado total o parcial con medidas para minimizar los riesgos valorados por el CEDEX o sellado en última instancia. Lo que no puede es quedar así después de treinta y cinco años. No se pueden herir a este punto los sentimientos de portmaneros, unionenses y murcianos. Después de treinta y cinco años de desidia e ineptitud ministerial/gubernamental, no se puede llegar manu militari e imponer una solución que no lo es para quienes llevan más de medio siglo viviendo in situ todos los hechos narrados.

Without wishing to offer an opinion, I lack the scientific training to allow such a thing. I believe that, given the entire terrible history that should never have occurred—the greatest environmental catastrophe in the Mediterranean caused by human intervention, with no accountability ever held for this fact, something also incomprehensible—I think it would make sense for an independent and neutral Study Center, preferably not Spanish, to make another assessment of the options that have been considered, including total or partial dredging with measures to minimize the risks assessed by CEDEX, or ultimately sealed. What cannot be done is for it to remain like this after thirty-five years. The feelings of the people of Portman, Unión, and Murcia cannot be hurt at this point. After thirty-five years of ministerial/governmental apathy and ineptitude, one cannot arrive manu militari and impose a solution that is not suitable for those who have been living in situ all the events described for more than half a century.

Mi visita a Portmán My visit to Portmán

Ginés Ortiz, el alcalde pedáneo de Portmán, vino a recogerme a La Unión. El camino a Portmán atraviesa esa parte de la sierra minera, donde pueden apreciarse de forma dramática las cortas y cráteres de las extracciones a cielo abierto. Antes de llegar al pueblo, paramos en el Club Náutico de Portmán, situado en un alto. Allí nos mostraron una serie de documentales realizados en 2009 que recogen las distintas fases de la historia. Puedo asegurar que la imagen que más me impactó fue la de la tubería saliente del lavadero Roberto vertiendo ese material viscoso y negro, 7.000 toneladas diarias sobre la bahía. “Las capas de arena del sellado, -me dice Ginés- llegarían a esta altura, tendrían un espesor similar a un edificio de veinte pisos”.

Ginés Ortiz, the mayor of Portmán, came to pick me up in La Unión. The road to Portmán crosses this part of the mining mountain range, where the cuts and craters from the open-pit mining can be dramatically appreciated. Before reaching the town, we stopped at the Portmán Yacht Club, located on a hill. There, they showed us a series of documentaries made in 2009 that capture the different stages of the story. I can assure you that the image that struck me most was the protruding pipe from the Roberto wash house pouring that viscous, black material, 7,000 tons a day, into the bay. «The layers of sand from the seal,» Ginés tells me, «would reach this height, they would be as thick as a twenty-story building.»

Bajamos a Portmán, pasamos por la Casa de Miguel Zapata, Tío Lobo, el empresario más rico de la sierra minera de Cartagena – La Unión. La casa es una de las joyas modernistas fruto de la prosperidad y de las condiciones laborales de bajos salarios, pagos en especie y mano de obra infantil. Murió en 1918.

We descended to Portmán and passed by the house of Miguel Zapata, Uncle Wolf, the richest businessman in the Cartagena mining mountain range—La Unión. The house is one of the modernist gems, a product of prosperity and working conditions: low wages, in-kind payments, and child labor. He died in 1918.

Museo Arqueológico Romano / Roman Archaeological Museum.

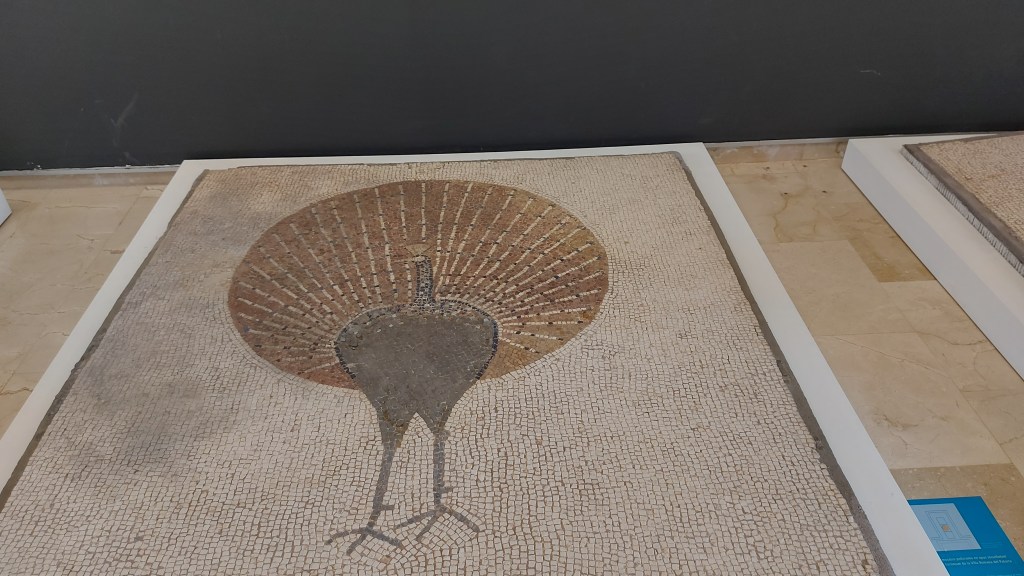

Portus Magnus fue fundada en el siglo I d.C. en una bahía semicircular de 1.200 metros de ancho y 840 de bocana al sur. El puerto fue uno de los tres españoles más importantes del Mediterráneo por su fondeadero abrigado donde las galeras se cargaban con el mineral de plata, plomo y cobre para su exportación. De las piezas depositadas en el museo destacan el mosaico del pavo real, entre otros mosaicos procedentes de una villa romana, la excelente muestra de ánforas de cerámica y los utensilios procedentes de la minería.

Portus Magnus was founded in the 1st century AD in a semicircular bay 1,200 meters wide with a southern entrance of 840 meters. The port was one of the three most important Spanish ports in the Mediterranean due to its sheltered anchorage where galleys loaded silver, lead, and copper ore for export. Among the pieces housed in the museum are the peacock mosaic, among other mosaics from a Roman villa, the excellent display of ceramic amphorae, and mining tools.

Observo a mi guía que no hemos visto ni rastro de lo que fue la bahía. Hacemos varios kilómetros de carretera y llegamos a una pequeña cala con su playa, hoy domingo llena de bañistas. Y un pequeñísimo puerto a la derecha. Algo mínimo y lejano al pueblo. Nada que ver con la desaparecida bahía de los tiempos romanos.

I point out to my guide that we haven’t seen a trace of what the bay once was. We drive several kilometers and arrive at a small cove with its beach, today Sunday filled with bathers. And a tiny harbor on the right. A tiny little thing, far from the town. Nothing like the vanished bay of Roman times.

Una desolación. Homo homini lupus. Nunca mejor dicho.

A desolation. Homo homini lupus. Never better said.

Descubre más desde LA AGENCIA MUNDIAL DE PRENSA

Suscríbete y recibe las últimas entradas en tu correo electrónico.